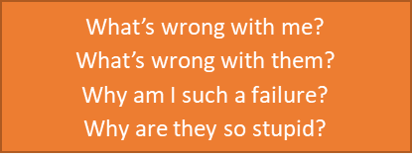

How often have you been working with a team or with a collaborative of organizations and been surprised by the end of a meeting with the direction it has gone or that it hasn’t really gone anywhere? How often have you been in a team or collaborative and not felt heard? How often have you not heard others?

Humans have been working together to solve problems, create new things, and explore our surroundings for our entire history. So why is it such a struggle? Susan Cain in her book, Quiet: The Power of Introverts argues that in the last century or so, we have bought into a belief that a particular type of personality and way of working together is ideal. And part of that ideal is a belief in collaboration above individual contributions.

Shawn Achor (who’s thought leadership we have explored in a previous post) in his second book: Before Happiness, suggests that the first person to speak generally sets the tone. Susan Cain, concurs and argues that when groups work together, we tend to fall into what she terms the New Groupthink.”The New Groupthink elevates teamwork above all else. It insists that creativity and intellectual achievement come from a gregarious place.” For a quick introduction to this concept, check out this 2012 NYT Sunday Review by Susan Cain.

Cain argues that this New Groupthink is subject to the same failures some psychologists have noted in group brainstorming including social loafing, production blocking, and evaluation apprehension. Production blocking is similar to Shawn Achor’s argument that the first person who speaks sets the tone. Only one person can talk at a time. Social loafing notes our tendency to abdicate our responsibility when others speak up, and of course most of us fear looking foolish in front of others which some psychologists term evaluation apprehension.

In a group setting where decisions are being made, we have a tendency to follow the answers of others. Gregory Berns at Emory University updated a classic study of groupthink using fMRI scanner to study subjects’ brains when they conformed to or broke with group opinion. They found that when we solve problems on our own, we use the parts of our brain that help us to solve that problem (in this experiment, occipital and parietal cortices for visual and spatial reasoning and the frontal cortex for decision making).

When we solve problems in groups and collectively come to the wrong answer, one would think that our frontal cortex (decision making) would light up more than our occipital and parietal coritices if we were consciously just going along with the wrong answer. What they found though was that our occipital and parietal cortices lit up as well. In other words, our perception of the problem changes to fit the group’s perception. This happens without us consciously deciding to go along with everyone else. Our very understanding of the issue and the solution change based on what one or more vocal participants think.

Susan Cain sums up the study by saying, “Most of Berns’ volunteers reported having gone along with the group because “they thought that they had arrived serendipitously at the same correct answer.” They were utterly blind, in other words, to how much their peers had influenced them.”

Bob Frick, in a Washington Post column used the term herding to describe this phenomenon.

This is even more concerning to those of us who work with teams and collaboratives in guiding their decision making. Not only are there conflict, territorialism, and trust issues in collaboration, but even when a group comes to the same conclusion, that conclusion may be faulty.

How do we hedge against such a threat to our collective decision making? Susan Cain provides a partial answer. She explores through multiple examples the importance of deliberate practice and personal space. I highly recommend reading her book for more details (particularly chapter 3).

One of her recommendations addresses the use of online collaboration. She provides some compelling arguments that the typical pitfalls of the New Groupthink are diminished when teams work in their own individual personal spaces but connect via technology.

“The evidence from science suggests that business people must be insane to use brainstorming groups,” writes the organizational psychologist Adrian Furnham. “If you have talented and motivated people, they should be encouraged to work alone when creativity or efficiency is the highest priority.” The one exception to this is online brainstorming. Groups brainstorming electronically, when properly managed, not only do better than individuals, research shows; the larger the group, the better it performs.” She extends this argument to include positing that academic researchers working from different locations collaborating electronically, produce more influential research than those who work alone or who collaborate face-to-face.

These arguments are intriguing in looking at how teams within an organization and organizations within a collaborative may best reduce the impact of the New Groupthink while leveraging the impact of collaboration.

When I work with organizations on strategic planning processes, I typically begin with interviews of stakeholders. I send the questions ahead of time. This provides individuals a chance to think through their answers before meeting with me either face to face or over the phone. Introverts have a chance to reflect and the interviews give me a chance to better understand the organization as a whole before having the stakeholders in a room together where group dynamics have an impact. I am able to learn not just about the traditional strengths, barriers, and opportunities for the organization, but also about the personalities, potential areas of conflict, and emerging priorities.

As a key part of a strategic planning process is not just the decisions made, but also the sense of ownership of those decisions, I take my clients through a mission, vision, and values statement process in a half-day retreat. Ideally, these retreats include Board, staff, and a sometimes a few outside stakeholders. Whether they have mission, vision, and values statements or will use those statements, the process of working together to identify “who we are”, “who we want to be”, and “what we value” provides a foundation for making shared decisions around priorities, goals, metrics, etc. for their strategic plan.

I provide individual reflection time and paired conversations in which board and staff listen to one other person deeply on their thoughts before moving into small and whole group work. This time of bonding and creating a shared sense of purpose is important. It may well be subject to the vagaries of groupthink, but the organization also benefits from the sense of oneness, ownership of the work, and kinship with one another.

Based on the current discussion of groupthink and the impact on decision making, I am considering shifting how I approach the second half day retreat where stakeholders make strategic decisions around goals, objectives, metrics, etc to develop a process that provides more online input either before, during, or after a face-to-face retreat.

A colleague of mine who works with a wide variety of stakeholders from artists, to non-profit organizations, to government and business leaders has developed an interesting hybrid method for small meetings. While facilitating the discussion, she keeps a a Google doc open for note taking. She invites the members of the meeting to join her in the note taking. This provides introverts a chance to add content without speaking. It also provides a shared method of documentation that may hedge against social loafing, production blocking, and evaluation apprehension.

[yop_poll id=”4″]

In future posts, I will update you on pilots I conduct of hybrid models of face-to-face and online collaboration. In the meantime, join us for a discussion around strategies to address the barriers of groupthink in teams and collaboratives on LinkedIN: Discussion Group

Next week, we will explore the difficulties humans have with defining “us” and “them” and its impact on collaboration with the provocative question: When are we just pretending to collaborate?